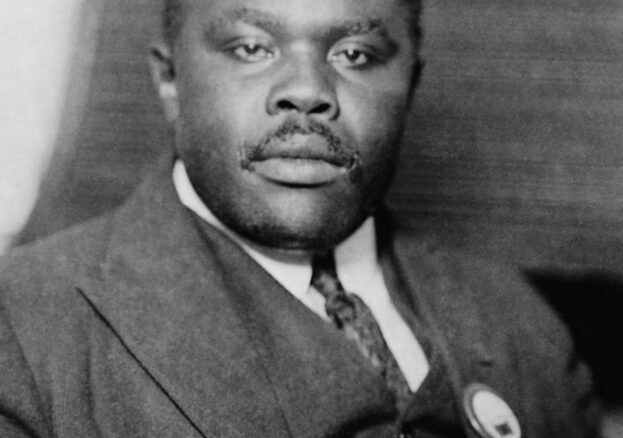

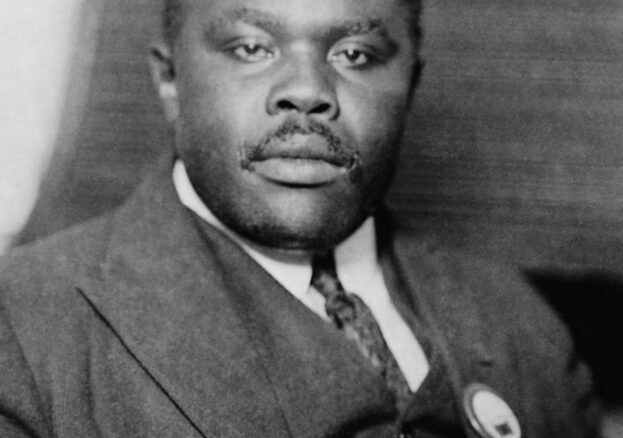

Marcus Garvey and his organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), represent the largest mass movement in African-American history.

Written by David Van Leeuwen ©National Humanities Center 01/02/2021

Considering the strong political and economic black nationalism of Garvey’s movement, it may seem odd to include an essay on him in a Web site on religion in America. However, his philosophy and organization had a rich religious component that he blended with the political and economic aspects. Garvey himself claimed that his “Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World,” along with the Bible, served as “the Holy Writ for our Negro Race.” He stated very clearly that “as we pray to Almighty God to save us through his Holy Words so shall we with confidence in ourselves follow the sentiment of the Declaration of Rights and carve our way to liberty.” For Garvey, it was no less than the will of God for black people to be free to determine their own destiny. His organization took as its motto “One God! One Aim! One Destiny!” and looked to the literal fulfillment of Psalm 68:31: “Princes shall come out of Egypt: Ethiopia shall soon stretch forth her hands unto God.”

Garvey was born in 1887 in St. Anne’s Bay, Jamaica. Due to the economic hardship of his family, he left school at age fourteen and learned the printing and newspaper business. He became interested in politics and soon got involved in projects aimed at helping those on the bottom of society. Unsatisfied with his work, he travelled to London in 1912 and stayed in England for two years. During this time he paid close attention to the controversy between Ireland and England concerning Ireland’s independence. He was also exposed to the ideas and writings of a group of black colonial writers that came together in London around the African Times and Orient Review. Nationalism in both Ireland and Africa along with ideas such as race conservation undoubtedly had an impact on Garvey.

However, he later remembered that the most influential experience of his stay in London was reading Booker T. Washington’s autobiography Up From Slavery. Washington believed African Americans needed to improve themselves first, showing whites in America that they deserved equal rights. Although politically involved behind the scenes, Washington repeatedly claimed that African Americans would not benefit from political activism and started an industrial training school in Alabama that embodied his own philosophy of self-help. Garvey embraced Washington’s ideas and returned to Jamaica in 1914 to found the UNIA with the motto “One God! One Aim! One Destiny!”

Initially he kept very much in line with Washington by encouraging his fellow Jamaicans of African descent to work hard, demonstrate good morals and a strong character, and not worry about politics as a tool to advance their cause. Garvey did not make much headway in Jamaica and decided to visit America in order to meet Booker T. Washington and learn more about the situation of African Americans. By the time Garvey arrived in America in 1916, Washington had died, but Garvey decided to travel around the country and observe African Americans and their struggle for equal rights.

What Garvey saw was a shifting population and a diminishing hope in Jim Crow’s demise. African Americans were moving in large numbers out of the rural South and into the urban areas of both North and South. As World War One came to an end, disillusionment was beginning to take hold. Not only was the optimism in the continuing improvement of humanity and society broken apart, but so was any hope on the part of African Americans that they would gain the rights enjoyed by every white American citizen. African Americans had served in large numbers in the war, and many expected some kind of respect and acknowledgment that they too were equal citizens. Indeed, World War One was the perfect opportunity for African Americans to fulfill Booker T. Washington’s requirement for equality and freedom. Through dedicated service in the armed forces, they could prove their worth and show they deserved the same rights as whites. However, as black soldiers returned from the war, and more and more African Americans moved into the urban areas, racial tensions grew. Between 1917 and 1919 race riots erupted in East St. Louis, Chicago, Tulsa, and other cities, demonstrating that whites did not intend to treat African Americans any differently than they had before the war.

After surveying the racial situation in America, Garvey was convinced that integration would never happen and that only economic, political, and cultural success on the part of African Americans would bring about equality and respect. With this goal he established the headquarters of the UNIA in New York in 1917 and began to spread a message of black nationalism and the eventual return to Africa of all people of African descent. His brand of black nationalism had three components—unity, pride in the African cultural heritage, and complete autonomy. Garvey believed people of African descent could establish a great independent nation in their ancient homeland of Africa. He took the self-help message of Washington and adapted it to the situation he saw in America, taking a somewhat individualistic, integrationist philosophy and turning it into a more corporate, politically-minded, nation-building message.

In 1919 Garvey purchased an auditorium in Harlem and named it Liberty Hall. There he held nightly meetings to get his message out, sometimes to an audience of six thousand. In 1918 he began a newspaper, Negro World, which by 1920 had a circulation somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000. Membership in the UNIA is difficult to assess. At one point, Garvey claimed to have six million members. That figure is most likely inflated. However, it is beyond dispute that millions were involved and directly affected by Garvey and his message.

To promote unity, Garvey encouraged African Americans to be concerned with themselves first. He stated after World War One that “[t]he first dying that is to be done by the black man in the future will be done to make himself free. And then when we are finished, if we have any charity to bestow, we may die for the white man. But as for me, I think I have stopped dying for him.” Black people had to do the work that success and independence demanded, and, most important, they had to do that work for themselves. “If you want liberty,” claimed Garvey to a meeting held in 1921, “you yourselves must strike the blow. If you must be free, you must become so through your own effort.”

But Garvey knew African Americans would not take action if they did not change their perceptions of themselves. He hammered home the idea of racial pride by celebrating the African past and encouraging African Americans to be proud of their heritage and proud of the way they looked. Garvey proclaimed “black is beautiful” long before it became popular in the 1960s. He wanted African Americans to see themselves as members of a mighty race. “We must canonize our own saints, create our own martyrs, and elevate to positions of fame and honor black men and women who have made their distinct contributions to our racial history.” He encouraged parents to give their children “dolls that look like them to play with and cuddle,” and he did not want black people thinking of themselves in a defeatist way. “I am the equal of any white man; I want you to feel the same way.”

Garvey organized his group in a way that made those sentiments visible. He created an African Legion that dressed in military garb, uniformed marching bands, and other auxiliary groups such as the Black Cross Nurses.

He was elected in 1920 as provisional President of Africa by the members of the UNIA and dressed in a military uniform with a plumed hat. At the UNIA’s First International Convention in 1920, people lined the streets of Harlem to watch Garvey and his followers, dressed in their military outfits, march to their meeting under banners that read “We Want a Black Civilization” and “Africa Must Be Free.” All the pomp brought Garvey ridicule from mainstream African-American leaders, but it also served to inspire many African Americans who had never seen black people so bold and daring.

While racial pride and unity played important roles in Garvey’s black nationalism, he touted capitalism as the tool that would establish African Americans as an independent group. His message has been called the evangel of black success, for he believed economic success was the quickest and most effective way to independence. Interestingly enough, it was white America that served as a prime example of what blacks could accomplish. “Until you produce what the white man has produced,” he claimed, “you will not be his equal.” In 1919 he established the Negro Factories Corporation and offered stock for African Americans to buy. He wanted to produce everything that a nation needed so that African Americans could completely rely on their own efforts. At one point the corporation operated three grocery stores, two restaurants, a printing plant, a steam laundry, and owned several buildings and trucks in New York City alone. His most famous economic venture was a shipping company known as the Black Star Line, a counterpart to a white-owned company called the White Star Line. Garvey started the shipping company in 1919 as a way to promote trade but also to transport passengers to Africa. He believed it could also serve as an important and tangible sign of black success. However the shipping company eventually failed due to expensive repairs, mismanagement, and corruption.

With all his talk of a mighty race that would one day rule Africa, it would have been foolish for Garvey to underestimate the power of religion, particularly Christianity, within the African-American community. The churches served as the only arena in which African Americans exercised full control. Not only did they serve as houses of worship but also as meeting places that dealt with social, economic, and political issues. Pastors were the most powerful people in the community for they influenced and controlled the community’s most important institution. Garvey knew the important place religion held, and he worked hard to recruit pastors into his organization. He enjoyed tremendous success at winning over leaders from almost every denomination. One of those clergymen, George Alexander McGuire, an Episcopalian, was elected chaplain-general of the UNIA in 1920. McGuire wrote the UNIA’s official liturgy, the “Universal Negro Ritual” and the “Universal Negro Catechism” that set forth the teachings of the UNIA. He attempted to shape the UNIA into a Christian black-nationalist organization. Garvey, however, did not want the organization to take on the trappings of one particular denomination, for he did not want to offend any of its members. McGuire left UNIA in 1921 to begin his own church, the African Orthodox Church, a black-nationalist neo-Anglican denomination that kept close ties with the UNIA.

The UNIA meetings at Liberty Hall in Harlem were rich with religious ritual and language, as Randall Burkett points out in his book Black Redemption: Churchmen Speak for the Garvey Movement. For even though Garvey rejected McGuire’s effort to transform the UNIA into a black-nationalist Christian denomination, he blended these two traditions in his message and in the form of his UNIA meetings. A typical meeting followed this order:

Garvey’s black nationalism blended with his Christian outlook rather dramatically when he claimed that African Americans should view God “through our own spectacles.” If whites could view God as white, then blacks could view God as black. In 1924 the convention canonized Jesus Christ as a “Black Man of Sorrows” and the Virgin Mary as a “Black Madonna.” Garvey used that image as an inspiration to succeed in this life, for African Americans needed to worship a God that understood their plight, understood their suffering, and would help them overcome their present state. Garvey was not interested in promoting hope in the afterlife. Success in this life was the key. Achieving economic, cultural, social, and political success would free African Americans in this life. The afterlife would take care of itself. Perhaps Garvey’s greatest genius was taking that message of material, social, and political success and transforming it into a religious message, one that could lead to “conversion,” one that did not challenge the basic doctrines of his followers but incorporated them into the whole of his vision. One of Garvey’s top ministers gave witness to the powerful effect of that message when he claimed in 1920, “I feel that I am a full-fledged minister of the African gospel.”

Garvey’s message of black nationalism and a free black Africa met considerable resistance from other African-American leaders. W.E.B. DuBois and James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP, and Chandler Owen and A. Philip Randolph of the publication Messenger, had their doubts about Garvey. By 1922 his rhetoric shifted away from a confrontational stance against white America to a position of separatism mixed with just enough cooperation. He applauded whites who promoted the idea of sending African Americans back to Africa. He even met with a prominent leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Atlanta in 1922 to discuss their views on miscegenation and social equality. That meeting only gave more fuel to his critics. In 1924 DuBois claimed that “Marcus Garvey is the most dangerous enemy of the Negro race in America and in the world.” Owen and Randolph, whose paper saw the race issue as one of class more than skin color, called Garvey the “messenger boy of the Klan” and a “Supreme Negro Jamaican jackass” while labeling his organization the “Uninformed Negroes Infamous Association.” The federal government also took an interest in Garvey and in 1922 indicted him for mail fraud. He was eventually sentenced to prison and began serving his sentence in 1925. When his sentence was commuted two years later, Garvey was deported to Jamaica. With his imprisonment and deportation, his organization in the United States lost much of its momentum. Garvey spent the last years of his life in London and died in 1940.

In my experience with undergraduates, I find that students know little if anything about Marcus Garvey. The simplest way to get their attention is to tell them that Garvey’s UNIA was bigger than the Civil Rights Movement, which most of them do know something about. Telling them that Garvey’s influence extended well beyond the borders of the United States to the Caribbean, Canada, and Africa may also pique their interest. Pointing out that Garvey’s message had a tremendous influence on later groups such as the Rastafarians and the Nation of Islam is also important. Much of what he said concerning racial pride and the potential for great racial success can be heard in later figures such as Malcolm X and even Stokely Carmichael, leader of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee). Garvey, Malcolm, and Carmichael are all considered more radical than the mainstream civil rights protesters, yet it was Booker T. Washington, someone considered quite conservative by most scholars, who had a profound influence on Garvey. Exploring that connection between the accommodationist philosophy of Washington and the black nationalism of Garvey and the other leaders might generate the most interest and help the students see the important place that Garvey holds in American history.

You might also bring up Garvey’s insistence that African Americans should see God, Jesus, and Mary as black. What is Garvey trying to do here? Why not throw out the religion of Christianity, which was used as a rationale for keeping slaves and viewing blacks as inferior people, and form a new religion that could communicate the hopes and desires of people of African descent? Why not do as the later group, the Nation of Islam, and remove all white influence? You might talk about Christianity itself, how blacks identified with so many of the stories of the Bible, the people of Israel, the suffering of Jesus, and how African American’s understanding of Christianity in many ways may already have been “black.” You might also talk about the role religion plays in a group such as Garvey’s. Why is religion so important here; why does it play any role at all? Why couldn’t Garvey simply preach black nationalism in economic, political, and social terms? What does religious expression do for people in an organization like the UNIA?

Scholars have debated the influence and relevance of Garvey, with assessments ranging from Garvey as little more than a demagogue whose uniqueness points to his irrelevance, to Garvey and his organization as earlier embodiments of the political battles of the 1960s. This debate is partly due to the fact that, until quite recently, sources for any study of the Garvey movement were difficult to obtain. Many were destroyed when the government deported Garvey, and some were lost in the air raids in London where Garvey spent the last years of his life.

An article that present a good summary of Garvey and his movement is Lawrence Levin’s “Marcus Garvey and the Politics of Revitalization” in Black Leaders of the Twentieth Century, edited by John Hope Franklin and August Meier (1982). For the religious aspects of the Garvey movement in the United States, look to Randall K. Burkett’s Black Redemption: Churchmen Speak for the Garvey Movement (1978) and Garveyism as a Religious Movement: The Institutionalization of a Black Civil Religion (1978).

The most important contribution to studies on Garvey is Robert A. Hill’s The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers (1983). Hill essentially brought the Garvey archive together by traveling the world and collecting every piece of paper he could find that had something to do with Garvey. He covers the UNIA’s activity in the United States, the Caribbean, and Africa. He explores the influence of Ireland and its struggle for independence on Garvey’s thinking and suggests that New Thought may have had some influence on Garvey as well. His general introduction and his more specific introduction, which are available online (see links) are outstanding and provide a concise summary of Garvey and the UNIA.

David Van Leeuwen earned his Ph.D. in religious studies from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.